Three summers and a thousand years ago. So begins the 1975 film The Man Who Would Be King. I’ve always liked this line. Especially now, in the age of Covid-19, when the passage of time seems to be doing strange things – accelerating one day and standing still the next – it helps me think about how some things seem so recent and yet so long ago. Now, on the cusp of finishing my dissertation in history, I’ve also been thinking back on my very first research project.

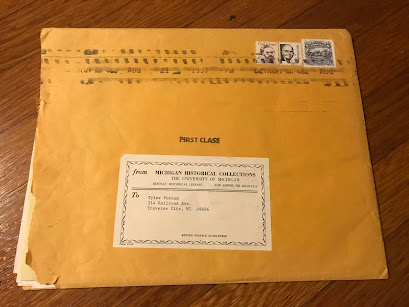

Twenty-three summers and a thousand years ago. I was nine in the summer of 1997, and my mother had decided that it was time for my brother and me to understand how to do research at the library. I’ve been interested in the Civil War for as long as I can remember, but I can’t remember how we chose the research project. Our goal was to find a Civil War soldier who was buried in our town who had left a diary we could read.That was easier said than done in 1997 in Traverse City, Michigan. Most of what I remember about that summer is inspired by a binder of papers that I’ve carefully preserved. Missing from that archive is a particular booklet I can picture quite clearly. Or perhaps it was a photocopy in a file at the library. It listed Civil War diaries and letters in state archival collections. I can only imagine that this is where we first found Horace Phillip’s name, associated with a diary at the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, and how we determined that he was from our town. We wrote away for a photocopy of the diary. It cost twenty cents a page. After postage and handling, the total came to $10.44. The Library mailed me a manilla envelope on August 21, 1997. And we wrote away for Horace’s pension records.

Meanwhile, based on my archive, I can see that we also consulted an array of books that I remember were held in the the Traverse City library’s “Nelson Room.” The room contained rare local history books and was a rather vaunted place to my mind as it was the exclusive domain of adults. You can see the library tags on the spines of books in my old photocopies. Michigan Men in the Civil War. Michigan in the War. I own some of those books now, but back then, before Amazon, and as a kid, the excitement of finding them on actual shelves was visceral. I also remember visiting the “town historians” in a book-filled office somewhere. I remember thinking that was the coolest job I could imagine. One of them even had a beard.

If I think about it, I can still feel the excitement of that summer of waiting. Knowing the forms you had completed were on their way to faraway libraries and not knowing when you would hear back or what you would get. Remember, this was still the age of the mail. Of photocopies and microfilm. Of taking photos and waiting with bated breath to get your roll of film developed and see what came out. We’ve lost so much of that world that it’s hard sometimes to even believe it was real, and to remember all the small joys that came with it.

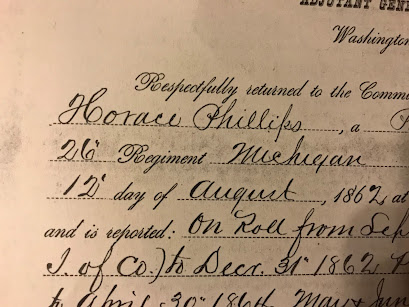

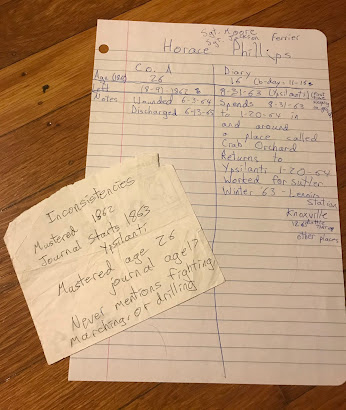

Horace Phillips’s pension records arrived. I must have struggled to read the script. I had only learned cursive in third grade, the year before. Now, many years later, after having spent countless hours reading eighteenth- and nineteenth-century handwriting, I can fly through these documents. In 1997, it would have been a foreign language. So what do they tell us about Horace?

Horace Phillips was a short man, 5’ 4½”. He had black hair and hazel eyes. He was 26 when he enlisted in the 26th Michigan Infantry on August 12, 1862 (158 summers and a thousand years ago). When I was nine, 26 must have seemed like a lifetime away; it was a lifetime away. Now, at 32, I wonder what it would have been like to join the army six years ago. It was the second summer of the war, and the enthusiastic young men of Horace's Company A – farmers, lumbermen, and clerks from Traverse City – nicknamed themselves with pride, the “Lakeshore Tigers.”

However obscure in the story of the Civil War, the Lakeshore Tigers would become a fixture in my life. At its best, local history reminds us who we are and guides our way. We care about these stories because of where we are from. Sometimes, in serendipitous ways, they haunt us. As part of that summer of research, based on some ephemera in my old binder, my mother must have looked up Civil War reenacting. As I’ve written elsewhere, this was near the peak of that hobby but before it flourished online, and it was rather hard to figure out how to become a reenactor (at least in northern Michigan). And I really wanted to be a reenactor. But I had to wait a bit.

A few years later, by a stroke of luck, a Civil War reenacting unit formed in Traverse City, and I joined. Like most units, we named ourselves after a specific local company from the 1860s. The Lakeshore Tigers. Reenacting with this unit changed my life: it brought me into the orbit of the people that inspired me to go to college to study Civil War archaeology. As my network widened, it was reenactors who introduced me to eminent scholars and researchers, wrote my reference letters for grad school, and helped me get jobs. I have my job today in no small part because of conversations I had at reenactments.

Horace Phillips’s war was a different experience, of course. I don’t know much about his personal journey, but I do know that the 26th Michigan served on guard details and skirmishes in Virginia, assisted in quelling the New York City “draft riots” of 1863, and entered the spring of 1864 as part of the Army of the Potomac and the new, cataclysmic campaign to end the war in Virginia. On June 3, 1864, at the Battle Totopotomy Creek, part of the General Ulysses’s S. Grant’s Overland Campaign, Horace Phillips lost the fourth toe of his left foot to a musket ball. He spent the rest of the war in hospitals, finally ending up at Mower Hospital in Philadelphia, not all that far from where I work today.

After the war, Horace moved around a bit. He farmed. He got married (to a Mary Antoinette). He had a son, named after his father, who went by Archie. He joined the Grand Army of the Republic, suffered from his war wound and the diseases of old soldiers: rheumatism, kidney failure, spinal issues. He died in October of 1915, as the world's next great war was just beginning.

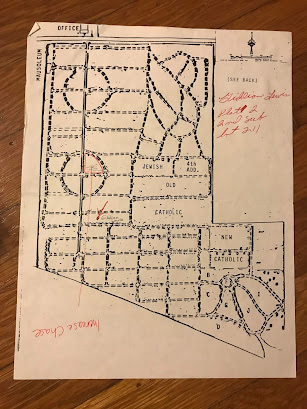

One of the things I remember about that summer of 1997 was the difficulty of locating Horace’s grave. Though he was listed in the rolls of the largest cemetery in Traverse City, Oakwood, even after consulting with the office and groundskeeper we were unable to locate his grave. Now, of course, you could confirm that with findagrave.com. Finally – and I don’t know exactly how – we found him buried in a small cemetery in the forgotten crossroads of Yuba, north of the city. He has a simple, government-issued headstone. I’ve visited him there a few times over the years.

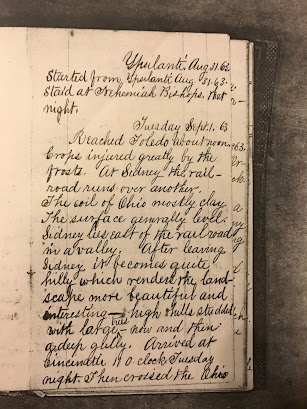

But what of his diary, the whole point of this research project? That’s where things got strangely more complicated. Reading the photocopies that arrived that faraway August today, I realize right away that it’s not the diary of the Horace Phillips I was after. This diary, though dating to 1863, is from a 17-year-old who went off from Ypsilanti, Michigan, to visit the army camps and ended up spending a few months as an assistant to a sutler, a vendor who sold things to the soldiers. But in 1997, I struggled to read the writing. I believed this must be the same man. After all, how many Horace Phillips from Michigan could there have been in the Civil War, anyway? I took notes, trying to puzzle out the differences. I never quite solved it. But I saved it, and all my notes. The first of my research files. Now my research files are mostly online, somewhere in the cloud. But there’s still nothing quite like holding things in your hands.

Some things I learned about research that summer are now quaint. Paper interlibrary loan slips. Microfilm. Waiting months for results. Our research world now moves at dizzying, digital speeds. Just this past month, I secured permission to use an image from an archive in Estonia in a matter of hours. Before the internet, I might not have ever known the image existed, much less been able to make contact or communicate with the archivists who care for it.

But so much of what I learned about research that summer is still with me. The detective work. The attention to detail. Even the frustration when your sources don’t align. Most of all, I still feel the sheer joy of being a historian. Of imagining what life was like once-upon-a-time, and of finding what bits of it might survive to help us imagine it better.

Horace Phillips – both of them, in fact – changed my life. But it was my mom who inspired this project. Her handwriting is on the pages in my old binder. She was the one who drove us around and showed us how exciting it was to discover things. These many years later, living half a country away and when I often shirk my duty and only talk to my parents every couple of weeks, I sometimes struggle to tell them how much they mean to me. They gave me the tools to craft a life doing something I love. Thanks, mom.

No comments:

Post a Comment