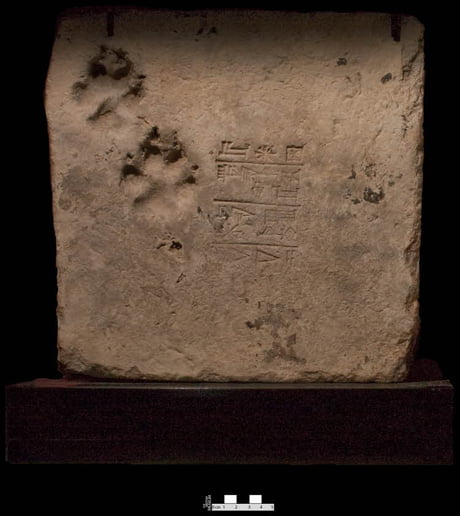

Examples of turkey droppings, a potter's fingerprint, a 16th-century Dutch kiln waster, and a 4000-year-old tile with a cat footprint from Ruby Lane, Ebay, the V&A, and here.

What could be more interesting than these little material signatures of some past failure? I far prefer flawed objects to perfect ones. And sometimes it's not accidental. Navajo rug weavers deliberately introduce flaws into their work. Japanese culture values wabi-sabi, an acceptance of natural imperfection. That sort of acceptance is not a strength of "Western" cultures, even if many people believe that perfection is best left to God.

A "spiritline" in a Navajo rug that Western eyes might read as an unacceptable imperfection. From the Smithsonian Museum of American History, here.

My most moving experience during a recent class I took on historic window restoration was when the craftsman leading the workshop was examining a century-old plate glass window and detected, in the awkward streak of glass on top of the pane's surface, evidence of an accident during production. "This is an amazing piece of glass," he said, staring into the pane, "See that streak, that odd blob? Someone messed up. That's someone in the shop tripping and accidentally throwing a bit of glass onto this finished pane." You could almost hear the echoes of a glassblower cursing his clumsiness across a century of time.

Since seeing it on my colleague Brenda Hornsby Heindl's blog in 2013, I've also coveted a particularly sculptural failure she acquired, a fused waster of mid-nineteenth century pipe heads uncovered on a kiln site in Ohio. This accident could hardly be more artistic, to my eye, if someone had tried to create it on purpose.

From Liberty Stoneware

In this case, however, I couldn't resist an ethical compromise. It's unfortunate that whoever dug Taber's kiln site doesn't seem to have left any record of what they found. But in this small artifact, we can see the shadow of an accident that happened 150 years ago. It reminds me that things rarely end up as we intend. It reminds us to look for the beauty in the imperfect. No good for smoking - no good for most anything in 1865 - this bit of trash, it turns out, is quite good for thinking.

No comments:

Post a Comment