Thanks to my colleague historian Matthew C. White and Grant Miller, the Historic Site Manager at Fort Montgomery State Historic Site, I'm happy to share a bit of information about one of my favorite things: archaeological textiles. Most such artifacts that we have from the 18th century survive as the result of specific formation processes, most often either because they landed in anaerobic (usually waterlogged) environments like shipwrecks and dense mud, or because they were in close contact with metal objects which helped preserve them. Once in a blue moon, fragments show up on regular old terrestrial digs for site-specific reasons that are hard (for me, at least) to explain.

Continental soldiers constructed Fort Montgomery as a defensive post on the Hudson in 1776. British, Loyalist, and Hessian forces captured it on October 6, 1777, and destroyed it a few days later. Beginning in 1916, sporadic archaeological projects investigated the fort. The most intensive excavations were done between 1967 and 1971 under a scholar named Jack Mead. You can read more about what these studies produced in "The Most Advantageous Situation in the Highlands": An Archaeological Study of Fort Montgomery State Historic Site, Charles Fisher, ed. (Albany, NY: The Cultural Resources Survey Program, New York State Museum, 2004).

In the summer of 1971, Mead's team was working in the North Redoubt of the fort (specifically in the five-foot square known as Section 50, Box L, Square 18B) when they uncovered a relatively large textile fragment alongside a few scattered pieces (now catalogued as A.FM.1971.346). At the time and occasionally since, various people have wondered whether the fragment was a coat or jacket sleeve, given its distinctive shape. The wool textile has at least two layers of a relativley coarse, plain weave of about 28 yarns to the inch. More recent examination by professional conservator Sarah Stevens did not detect any evidence of seams, stitching, or thread. The fragments were found in close proximinity with ten musket balls and a British uniform button. Some 262 musket balls and all sorts of other interesting objects were found in the Redoubt overall.

The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation was kind enough to share a variety of research material and the original excavation slides with me and grant permission for them to be published here. Here's the fragment in 1971 and in its current state and more recently. If you're sharp-eyed enough to notice that the extant fragment seems to be a mirror image of the original in situ, that's because it was apparently flipped over at some point into its current state in storage.

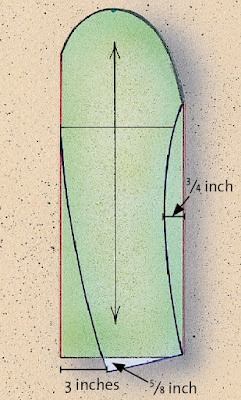

Indeed, it's pretty easy to see a sleeve-like shape here. Below, I've highlighted that shape and rotated the view of the fragment before it was lifted. If you aren't as used to seeing parts of clothing in flat pieces of fabric, this is approximately the shape of an "upper sleeve" with the "sleeve cap" at top and the cuff edge at bottom, and I've inserted an image of a modern upper sleeve pattern to help (note that period men's upper sleeves were close to but not quite this shape).

But, like most other folks that have puzzled over this object, I don't think it's a sleeve. It's hard to make any firm conclusions without seeing it in person, but there really doesn't seem to be any evidence for seams, hems, lining, or anything else besides its shape to suggest this identification. And the more I puzzle over the original excavation slide images, the more I think that you can see related fragments that originally extended past the misleading outline of a sleeve shape.

See what you think. Here's our pal again:

Now below, here's a great, in-focus closeup of the center of the fragment (key in on the large white object, apparently a cut root or sapling according to folks in the know, at the upper left corner here, which is in the upper center of the above image). I've crudely highlighted the weave directions of the upper layer (red) and the lower layer (blue) and also tried to emphasize how much the weave direction is wiggling a bit with the clearly not-parallel green lines that are nonetheless definitely in the same piece of fabric. This sort of movement happens readily in fabrics that are relatively loose or thin.

.jpg)